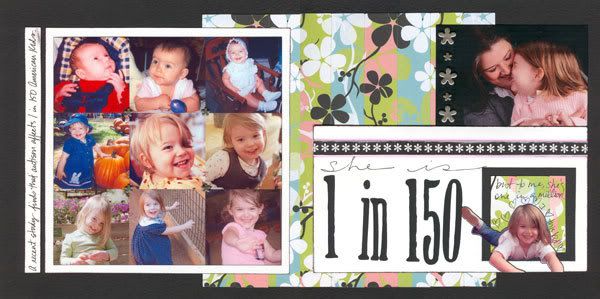

I just finished a layout for a circle journal I'm participating in; Kay's theme was "Bumps in the Road of Life." A tough topic, but the other entries in her book were very inspiring - and it felt good to write about this, to make a layout about it. Somehow it makes you feel more in control of the situation. Anyway, since the journaling is pretty long, I thought I would post it here on my blog instead of trying to scan it. Besides, I thought it would make a good blog entry: If what's good for the blog is good for the scrapbook, then what's good for the scrapbook is good for the blog, right? ;) I've posted a picture of the layout here too but if you want to see it in more detail you can see it in my gallery at 2Peas. I titled it "She is 1 in 150" because of the new study that found that autism affects 1 in 150 American children (read the article in the Wall Street Journal or at the Autism Speaks website). I hope that if you are moved by Hannah's story, you will consider sending a donation to Autism Speaks organization; donations received through this link by March 31, 2007 can help win a matching grant (click here for more details). So here is Hannah's story; she may be 1 in 150, but to me, she is 1 in a million...

Autism is one of those things that doesn’t happen to you. It’s one of those things that you read about, or you know someone who knows someone who has a kid with it. But it doesn’t happen to you, to your kids. Until it does.

Hannah was a perfect baby, always happy, always smiling, very loving. She hit every milestone in the baby books on time, if not early. Then she turned two, and though the “terrible two’s” really weren’t so difficult, the development of her language skills started languishing. Her social skills also stopped advancing, though I didn’t realize it at the time, having had no experience with other children with which to compare. All I knew is that most of the time, she was adorable, jabbering away in half-complete sentences and baby talk – and sometimes she was unbearable, throwing herself on the floor in violent screaming fits when she didn’t get her way. It was very stressful at times, but I figured, well, she’s only two; she’ll grow out of it.

Then she turned three, and she started attending Mother’s Day Out twice a week. After the first couple of months, her teachers expressed their concern to me that she was not as well developed linguistically and socially as her peers, and recommended that I have her tested for a developmental delay. I shrugged it off for a couple more months, partly waiting (and hoping) for her to simply “grow out of it,” and partly – I admit now – not wanting to even entertain the notion that something might be wrong with my precious baby girl. By the spring semester, though, even I could see that the gap between Hannah and her peers was widening, so I agreed to have her tested by the local school district. The evaluation team identified Hannah as having mild Pervasive Developmental Disorder (PDD) – an umbrella that includes autism spectrum disorders and Asperger’s Syndrome – and we arranged for her to start attending the Preschool Program for Children with Disabilities at our neighborhood elementary school in the fall.

After a long and difficult summer, fall finally arrived, and Hannah turned four shortly after school started. We made special arrangements that allowed her to attend Mother’s Day Out twice a week – all of her various caregivers agreed that it would be good for her to continue to have the exposure to “normal” children her age, as an example for her to emulate as well as a stimulus to her desire to grow. (The primary difficulty was that at four years of age, she is the only child in her MDO class not potty-trained, and the classroom is not set up for diaper changes and supervised bathroom trips.) She enjoys her mornings at MDO, but it is at preschool that the real work is done, and we were surprised and pleased to see rapid improvement in Hannah’s behavior and language skills in just the first six weeks.

I would not say that she is a “completely different child” (as you will often hear of children) – she remains as charming and delightful as she ever was. She is imaginative and amusing and beautiful and enthusiastic, and emanates a joyous warmth that seems to touch everyone who sees her. Yet the change in her from just a year ago is unmistakable, and remarkable: her sentences are longer and longer, and it has been months since I heard a syllable of baby talk. Her play-stories are more and more the product of her own fertile imagination, and less and less a mere repetition of the stories she knows from books and movies. She is learning to take turns and to share, and shows much more interest in doing things herself than in insisting that Mommy and Daddy wait upon her hand and foot. She is smart, learning to read and write, using logic to negotiate, and showing signs of a photographic memory. Best of all, she is starting to interact with other children, to call them by name, to talk to them and play with them; at home she likes to recite the list all of her friends to anyone who will listen.

There is still a long road ahead of us, though. She still has difficulty controlling her temper, especially when denied to have her own way, and she appears completely unaffected by any sort of external motivator or punishment. She has very little interest in toilet training and a very limited appetite. This winter, Hannah was evaluated by a psychologist, the summation of whose report was a single, concise word: conundrum. In all her years evaluating children, she has never seen one like Hannah, who appears normal and yet isn’t; who appears to be delayed and yet doesn’t. Her conclusion and professional opinion: Either Hannah is autistic or she is simply the most stubborn child this world has ever seen. Neither scenario sounds particularly appealing to me. Obviously, this is a “bump” that is going to take a long time to get across. In the meantime, I do what I can: I do my best to be a good wife and a good mother, I scrap, I go to church, I spend much-needed time with my girlfriends. I try to stay informed about autism research, the possible causes and treatments, and I am learning how to be my child’s advocate. I take one day at a time.

Hannah was a perfect baby, always happy, always smiling, very loving. She hit every milestone in the baby books on time, if not early. Then she turned two, and though the “terrible two’s” really weren’t so difficult, the development of her language skills started languishing. Her social skills also stopped advancing, though I didn’t realize it at the time, having had no experience with other children with which to compare. All I knew is that most of the time, she was adorable, jabbering away in half-complete sentences and baby talk – and sometimes she was unbearable, throwing herself on the floor in violent screaming fits when she didn’t get her way. It was very stressful at times, but I figured, well, she’s only two; she’ll grow out of it.

Then she turned three, and she started attending Mother’s Day Out twice a week. After the first couple of months, her teachers expressed their concern to me that she was not as well developed linguistically and socially as her peers, and recommended that I have her tested for a developmental delay. I shrugged it off for a couple more months, partly waiting (and hoping) for her to simply “grow out of it,” and partly – I admit now – not wanting to even entertain the notion that something might be wrong with my precious baby girl. By the spring semester, though, even I could see that the gap between Hannah and her peers was widening, so I agreed to have her tested by the local school district. The evaluation team identified Hannah as having mild Pervasive Developmental Disorder (PDD) – an umbrella that includes autism spectrum disorders and Asperger’s Syndrome – and we arranged for her to start attending the Preschool Program for Children with Disabilities at our neighborhood elementary school in the fall.

After a long and difficult summer, fall finally arrived, and Hannah turned four shortly after school started. We made special arrangements that allowed her to attend Mother’s Day Out twice a week – all of her various caregivers agreed that it would be good for her to continue to have the exposure to “normal” children her age, as an example for her to emulate as well as a stimulus to her desire to grow. (The primary difficulty was that at four years of age, she is the only child in her MDO class not potty-trained, and the classroom is not set up for diaper changes and supervised bathroom trips.) She enjoys her mornings at MDO, but it is at preschool that the real work is done, and we were surprised and pleased to see rapid improvement in Hannah’s behavior and language skills in just the first six weeks.

I would not say that she is a “completely different child” (as you will often hear of children) – she remains as charming and delightful as she ever was. She is imaginative and amusing and beautiful and enthusiastic, and emanates a joyous warmth that seems to touch everyone who sees her. Yet the change in her from just a year ago is unmistakable, and remarkable: her sentences are longer and longer, and it has been months since I heard a syllable of baby talk. Her play-stories are more and more the product of her own fertile imagination, and less and less a mere repetition of the stories she knows from books and movies. She is learning to take turns and to share, and shows much more interest in doing things herself than in insisting that Mommy and Daddy wait upon her hand and foot. She is smart, learning to read and write, using logic to negotiate, and showing signs of a photographic memory. Best of all, she is starting to interact with other children, to call them by name, to talk to them and play with them; at home she likes to recite the list all of her friends to anyone who will listen.

There is still a long road ahead of us, though. She still has difficulty controlling her temper, especially when denied to have her own way, and she appears completely unaffected by any sort of external motivator or punishment. She has very little interest in toilet training and a very limited appetite. This winter, Hannah was evaluated by a psychologist, the summation of whose report was a single, concise word: conundrum. In all her years evaluating children, she has never seen one like Hannah, who appears normal and yet isn’t; who appears to be delayed and yet doesn’t. Her conclusion and professional opinion: Either Hannah is autistic or she is simply the most stubborn child this world has ever seen. Neither scenario sounds particularly appealing to me. Obviously, this is a “bump” that is going to take a long time to get across. In the meantime, I do what I can: I do my best to be a good wife and a good mother, I scrap, I go to church, I spend much-needed time with my girlfriends. I try to stay informed about autism research, the possible causes and treatments, and I am learning how to be my child’s advocate. I take one day at a time.

Hello! I came across your blog from a comment you left on Ali Edwards' blog! I saw the wonderful scrapbook page you made of your daughter, and something you said really stuck out at me: How can a child appear to be normal and autistic at the same time? My daughter Reece (who will be 5 in 2 short weeks) is so much like that! In fact, most people who meet her now would never believe that she has a diagnosis of PDD-NOS and that 2 years ago she had no functional language and only potty trained last summer. Sometimes I even find myself wondering if I'm nuts when I say that she has high-functioning autism! :)

ReplyDeleteAnyway, just had to comment! Hang in there!

Jennifer